The figures illustrating the impact of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are staggering. Depending on how you define PFAS, it could be more than seven million different substances that make up these toxic ‘forever’ chemicals (and counting). Over 330 wildlife species are known to be affected across every continent, and those are only the ones that have been studied. PFAS are everywhere: our soil, rivers and even our bloodstreams.

The scariest figure is the proposed cost to remove and destroy all PFAS-related chemicals — it’s more than the global GDP. The presence of PFAS can add massively to the cost of construction projects. For example, the Belgian Oosterweel project has seen major delays and cost increases, with PFAS contamination being cited one of the main reasons.

There’s no doubt about the impact and scale of the PFAS problem. The solution starts with driving global awareness as a priority, but the most critical step is the sharing of best practices, research and innovation in PFAS management, especially within assessment, remediation and supply chain removal. The urgency behind this is rapidly growing, with new, stricter regulations and rulings being outlined worldwide, starting with the U.S. and parts of Europe, with many more countries to follow, and the rise in the understanding around liability.

It’s in this complex, shifting challenge where Jane Thrasher, award-winning director of land quality and ground contamination and community of practice global lead, thrives. As a geologist with a PhD in applied geochemistry, Jane has 35 years of experience leading the industry, having worked on technically complex and challenging land quality projects across nearly every sector and constantly driving innovation and tech-led change. She was named Technical Lead of the Year at the Brownfield Awards 2024.

Creating and sharing best practices in PFAS management is what Jane excels at, and it’s precisely what’s needed to draft a blueprint for markets in the U.K. and Europe. Here are four of her proven PFAS insights.

- Industry success hinges on iterative, cross-sector partnerships.

PFAS have been emerging as contaminants of concern within our industry for the last 20 years, but I started getting involved in late 2019 when we had an opportunity to bid for work with the UK Environment Agency. This was a small initial feasibility study looking at developing a risk screening tool for PFAS and understanding where their highest risk sites might be. It was exciting for us as we combined PFAS know-how and contaminated land risk assessment with the power of Geographical Information Systems (GIS) for the first time, on a national scale.

Our first study really impressed our client and over the last four years, thanks to collaboration and shared technical input from the Environment Agency, digital mapping providers, laboratory services and other industry partners, we have successfully created an effective GIS-based risk screening tool. The PFAS Risk Explorer enables a consistent approach to the screening of thousands of potential PFAS source sites across England, using multicriteria assessment to score sites based on national mapping and taking account of water quality surveillance monitoring. It helps operational staff relate water quality monitoring data to sources and pathways. The project has grown exponentially in scale, impact and funding throughout the phases. We have won a couple of internal ‘Beyond Excellence’ awards for it, recognizing our demonstration of Jacobs’ commitments, including technical excellence, innovation and inclusion. Very recently, we were delighted to be ‘Highly Commended’ in the ‘Best Research, Innovation or Advancement of Science in the Brownfield Sector’ category at the Brownfield Awards 2024.

Beyond the project’s growth and impact, one of the biggest benefits is the fantastic relationship we’ve built with the Environment Agency, learning together on our PFAS journey. It has influenced the way forward. It’s also a blueprint for other clients and other sectors — including the water and aviation sectors. Even though we’re waiting on regulation changes in some cases globally, we’re seeing a rising demand for an integrated, systems-level approach for tackling PFAS in a programmatic way, not just in single projects. Success there will rely on partnerships like ours with the Environment Agency.

- Global Communities of Practice (CoPs) are key differentiators for faster problem-solving.

While many companies have experts globally, it’s the processes, access and collaboration that turn a capability into a competitive edge. I’ve been working collaboratively now for nearly 30 years, but I’ve never seen the level of interaction that we have now within Jacobs’ CoPs. The CoPs include regular webinars for professional development and information sharing and are an excellent forum for educating the next generation.

I can post a question in the PFAS channel of the Emerging Contaminants CoP at five in the evening London time, and by the time I have logged back into work at eight the next morning, I will have a host of different answers and technical viewpoints and references from Australia, New Zealand or North America. The critical difference now is that these experts give their opinions in real time because they’re curious and invested in the question. They want to give answers and provide track record insights immediately — they don’t want to wait for appointments and follow-up meetings.

This speed and instant knowledge transfer is so valuable: it’s a lesson for the rest of the industry. This CoP has also resulted in published research that helps drive the industry forward. One of the best examples is a paper on the implications of PFAS groupings in contaminated sites, and it was published in Remediation. It was led by my colleague, Karl Bowles, but it drew on the combined expertise across our company and time zones as well as leaders in PFAS from around the world.

- PFAS are borderless and mobile, requiring a collective, catchment-level approach.

One of the greatest challenges with PFAS contamination is that it doesn't stick to clients and sites. PFAS are persistent, mobile and ubiquitous. For example, suppose we’re dealing with fire-fighting foam containing PFAS at airports. In that case, those chemicals don’t just affect the airport site — the chemical discharge can also affect nearby rivers and the groundwater outside the site. It then becomes an issue for water companies and utilities abstracting water from rivers or groundwater.

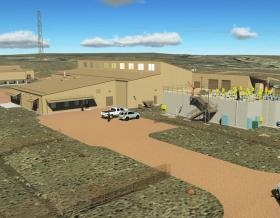

The answer requires a more holistic approach that understands all the liabilities and responsibilities involved and harnesses the right talent and technology to solve the different sector challenges within each catchment. For example, we are using several successful processes in one of our recent PFAS from fire-fighting programs in Ontario, Canada, the Jack Garland Airport Remediation Project, to help improve the health and safety of the City of North Bay. These processes included the removal and treatment of the most contaminated soil at the airport, the injection of adsorptive material along property boundary to treat exiting groundwater, and the placement of adsorptive material at exit locations to prevent PFAS in surface water from migrating downstream. It’s these kinds of tailored processes that help solve the PFAS issues within project borders.

The biggest lesson here is that the solution to PFAS in the U.K. or Europe (or globally) can’t be provided by one company or individual actions; it requires innovation and collaboration across the whole industry — it all starts with accurate evidence gathering, harnessing best practice and providing a robust data foundation.

We have recently completed a short piece of work looking at PFAS uncertainty over the next five years and potential mechanisms to mitigate the economic impact for one water company; this expanded to be a collaborative approach involving a total of ten water companies in England and Wales. The project required an interdisciplinary collaborative approach with expertise in PFAS assessment, regulation, permitting, treatment and management. We integrated our local knowledge of the regulatory system and what has been happening with regards to PFAS over the last five years, with global trends and advice from global PFAS experts.

One of the biggest challenges in gathering data is cost. The costs are still very high for monitoring and sampling (for example, analysis of one water sample can cost more than £250, and one project can require hundreds of these sample analyses; water companies have so far provided the Drinking Water Inspectorate with the results of over one million PFAS tests). In almost all cases, airports and water companies haven’t budgeted for these costs, but it must be integrated into future planning as this evidence-gathering is critical for understanding and dealing with the PFAS problem.

- Better evidence is critical for more accurate risk assessment.

One of the (many) problems with PFAS is that they're of concern at incredibly low concentrations within water. In most cases, treatment targets require reduction of concentrations down to the nanogram level. However, water treatment deals with many different types of contaminants (with differing treatment processes) and huge, variable amounts of water are processed daily. If we’re trying to get things down to the nanogram level, other materials, such as organic matter, can inhibit the treatment.

The complexity of that challenge rules out the use of current simple, off-the-shelf treatment systems. Jacobs is working on this set of solutions globally, including our proprietary site evaluation toolset that maps hundreds of PFAS transformation pathways under environmentally relevant conditions and identifies different PFAS sources and release histories.

The successful development of PFAS solutions requires a deep understanding of the treatment dynamics and a much better evidence-based grasp of PFAS behaviors and the state of the groundwater sources. PFAS all behave differently. Some are more mobile while others stick to organic matter, different PFAS accumulate in different parts of the human body. They also have different sources. All of this contributes to making risk assessment highly technical and challenging, but the more data and experience we gain, the better equipped we are to win the PFAS battle.

Conclusion

PFAS are a growing, formidable threat and undoubtedly one of the greatest challenges in our lifetimes, but they also offer one of the greatest opportunities for innovation and collaboration. Creating a better long-term, holistic solution for the U.K. and Europe hinges on learning from best practices globally, defining risk accurately and harnessing the best talent and technology in the right way.

About the author

Jane Thrasher is a geologist, environmental consultant and project manager with nearly 35 years’ industry experience, a staggering 29 of which have been at Jacobs. She is a Director of Land Quality and is Jacobs’ Ground Contamination and Land Quality Community of Practice Global Lead. Jane has worked on technically complex and challenging land quality projects across nearly every sector. She has a long track record of delighting clients and colleagues with her deep subject matter expert knowledge and consistent drive for excellence, inclusion, diversity, safety and wellbeing.

Jane is well known and active in the wider U.K. contaminated land community; in recognition of her accomplishments, she was named Technical Lead of the Year at the Brownfield Awards 2024.